For me, language access has always been important. I had a Deaf cousin, my family finger spelled and used basic signs, and I had a passion for inclusion.

At the age of 4, after watching the Miracle Worker, a movie about the early life of Helen Keller, I apparently announced to my mother that I was going to be an interpreter “when I grew up”. Considering I also wanted to be a professional mountain climber and a hot air balloon pilot, nobody thought it would come true.

But I threw myself into learning Auslan and Signed English, went to every interpreted performance and Deaf gathering I could find and in 2001 I completed the Diploma of Interpreting (Auslan-English). In 2002 I became a NAATI Paraprofessional Auslan-English interpreter and that 4-year-old girl’s prediction came true.

My early career was mostly spent working with Deafblind people who signed in Tactile Auslan or Tactile Fingerspelling. I also worked with Deaf people in community settings, for TAFE, health care, employment but my favourite early career setting was the Deaf school at North Rocks where I was privileged to work with Deaf children and teachers in an Auslan-English bilingual immersive environment.

I gained my Professional Auslan-English NAATI accreditation in 2005, thanks to some mentorship and encouragement from the principal at the school at the time and then my employment settings opened up. But in the forefront of my mind was always equity, access and holding space for the communities I worked with.

Over time I discovered the fields I enjoy and work best in and I would like to share some with you.

I have spent time as a designated interpreter working with several Deaf professionals. In this role, designated interpreters interpret in formal and informal contexts, and are also in a position to learn the appropriate language and interaction structures according to the various contexts they work. This means the Deaf professionals and interpreters have a very collaborative working relationship unlike other typical settings.

I also work with Deaf Interpreters. If you’re not familiar with this term, Deaf interpreters are themselves Deaf, usually native signers, and they are not only trained in the interpreting process but (in the Australian context) are also skilled in message transfer between Auslan and another sign language, a tactile language or a highly visual communication method for clients who do not have access to standard or shared language. I have worked in a Deaf-Hearing interpreter team in settings such as counselling, immigration, medical, workshops and conferences.

While there is no formal NAATI Auslan-English translation test, I have been trained to work in the translation area. If a text is being produced for a Deaf audience to view, I have been on a team where I produce a translation text which is then performed or signed by a Deaf person, or someone with more experience in translation performance. Unlike written translation, sign translation teams cannot be divorced from the final text as someone has to be on screen and visible to the audience and therefore it is important that the right person is selected to be the face of the translation. It has been great to see more Deaf people take up roles in translation in more recent years as well!

Where spoken language interpreters can work remotely via telephone interpreting, Auslan interpreters work remotely via video conferencing software like Zoom, MS Teams, Webex and even Facetime. Moving from face-to-face environments to online spaces means that our receptive access to Auslan goes from 3D to 2D and it can take practitioners time to adjust. I relish the challenge of online interpreting and have been fortunate to be able to mentor colleagues who are newer to this space so they can feel more confident working in a 2D environment.

Auslan has gained a lot of visibility in the last three years with the Black Summer fires, followed by floods, followed by COVID-19, and then more floods. And this is perhaps where most people recognise those of us who worked as part of the various media interpreting teams from all around Australia. Again, unlike spoken language interpreting Auslan interpreters have to be visible in order for the message to be seen and as a professional who has aimed her entire life to be as unobtrusive as possible, and be just “part of the furniture”, being recognised when you’re out to dinner or when you arrive at an assignment is awkward, but I guess it’s great that at least language and communication access is in people’s minds right now.

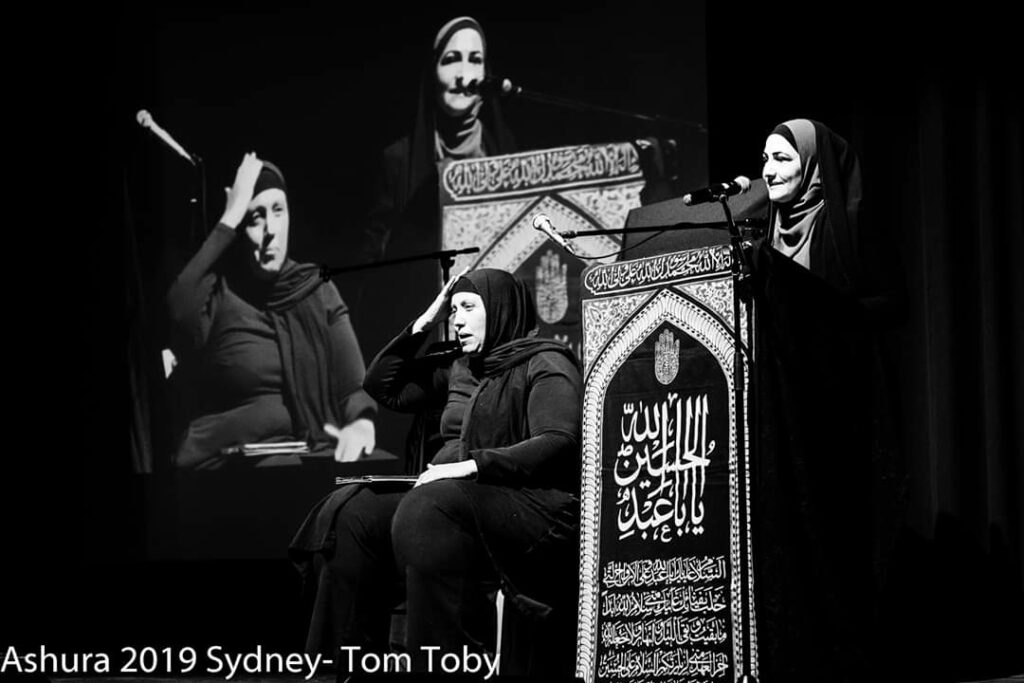

Recently, I have begun working in an exciting space: working with Deaf Muslims in religious settings such as mosques, Islamic centres and jurisprudence classes. This interpreting context comes with several challenges: I am not Muslim so I have had to learn about the religion, I did not speak Arabic (and my Arabic fluency is still on the ground floor) which meant the constant code-switching between English and Arabic in the source text was something to overcome. Because Deaf Muslims hadn’t had access to religious teachings, there wasn’t any developed vocabulary for the terms I was interpreting to them. So we have worked together to develop new vocabulary, borrowing some signs from overseas languages where appropriate. This emerging community in Australia has Deaf people from at least 11 different countries and it is an honour to work with them as part of the small team of practitioners interpreting on a weekly basis in this space.

I have been honoured to be present in so many moments of people’s lives as their interpreter; literally from cradle to grave. Providing communication access is such a privilege. With a Master of Translating and Interpreting under my belt, this year I have embarked on the toughest piece of work yet. In order to give back to the community I work with, and those who invested in me so I could become a better interpreter, I am now studying a Master of Research with the hope that I will be able to add new knowledge and new perspectives to interpreters who are working with Deaf people.

Rebecca Cramp is a Certified Interpreter in Auslan and English.